Harold

Hadley Copeland (1860–1926)

"The shocking discoveries made since

we first opened the tomb should be more than enough to inform us. The knowledge

lingering in those ancient tablets may wither our souls."

-From

the Introduction to “The Zanthu Tablets: a Conjectural

Translation”

A noted anthropological researcher and co-founder

of the Pacific Area Archaeological

Association (PAAA), of which he later became the president. He began his

studies in Cambridge, later graduating from Miskatonic University. He travelled

widely throughout Asia in the 1890s and his published journals of these trips

gained him some popularity. His early scholarly writings include “Prehistory in the Pacific: A Preliminary

Investigation with References to the Myth Patterns of South-East Asia”

(1902), “Polynesian Mythology, with a

Note on the Cthulhu Legend-Cycle” (1906), The Ponape Scriptures (1907) (his translation of a document

discovered in 1734), “The Ponape Figurine”

(1910) and “The Prehistoric Pacific in

light of the Ponape Scriptures” (1911). This last work met with

considerable disfavour and he was forced to resign his presidency of the PAAA as a result.

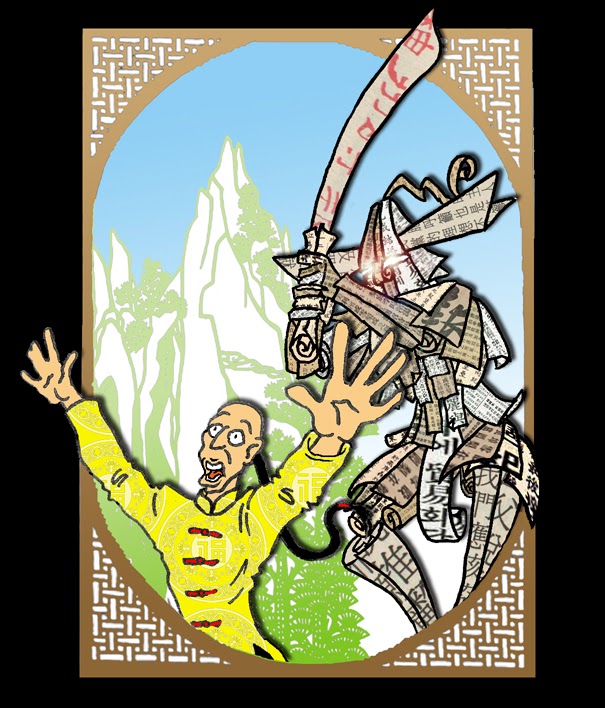

In 1913, Copeland took a different tack and set off

on an expedition to Central Asia, in search of the Plateau of Tsang. The Copeland–Ellington Expedition met

with disaster from the outset: Ellington died in mysterious circumstances after

only a few days and the group’s guides and bearers either deserted, or perished

from the harsh conditions. Three months later, Copeland was found raving in

Mongolia, claiming to have encountered a Muvian wizard named ‘Zanthu’, who gave

him ten inscribed stone tablets. These tablets were in his backpack when he was

discovered, covered with ancient hieroglyphics.

After returning from his ordeal, Copeland spent the

next three years translating the tablets and published his findings as The Zanthu Tablets: A Conjectural

Translation; he was then confined to an asylum in San Francisco where he

slit his own throat shortly afterwards. His vast collection of papers and

Polynesian artefacts was left in his will to the Sanbourne Institute of Pacific Studies.

(Source: Lin Carter, “The Dweller in the Tomb”)

“Prehistory in the Pacific: A Preliminary

Investigation with References to the Myth-Patterns of Southeast Asia”

A relatively innocuous monograph,

attempting to resolve archaeological phenomena found in the Pacific region with

the mythography of the Southeast Asian margin of the ocean. While not outlining

clear connexions between legend and phenomena, the paper provides sound

procedures for using mythology to provide rationales for cultural behaviours

and taboos.

English; Harold H. Copeland; 1902; 1/1d2 Sanity

loss; Cthulhu Mythos +1 percentiles; 4 weeks to study and comprehend

Spells: None

“Polynesian Mythology, with a Note on the

Cthulhu Legend-Cycle”

Still in academically tepid waters,

Copeland tries in this paper to connect several articles and journals published

by the Miskatonic Press with the

studies already undertaken by the PAAA.

In the course of his analysis he finds great sympathy with the work of George

Angell and Francis Wayland Thurston and sceptically probes the implications of the

so-called “Worldwide Cthulhu Cult”. His conclusions weigh heavily on the side

of there being enough parallelism amongst mythology for the paranoid observer

to construct any kind of bizarre scenario; however, he does leave many

suggestive coincidences unresolved.

English; Harold H. Copeland; 1906; 1/1d3 Sanity

loss; Cthulhu Mythos +3 percentiles; 8 weeks to study and comprehend

Spells: None

The Ponape Scriptures

The original

copy of this work was discovered in the Carolinas by Captain Abner Exekiel Hoag

in 1734. It was scribbled upon a series of dried palm leaves protected by a

frame made from the wood of an extinct cycad. With the help of his servant “Yogash”,

Hoag translated the text: some say that Hoag wrote the material himself after

talking to the natives; as the original is written in hieratic Naacal, a

language which should not have been available either to Hoag or his servant,

this point of view is somewhat ameliorated (if only by the existence of the actual

text).

Hoag’s attempts

to publish the work, which seemed designed for missionary purposes, were

thwarted by the religious leaders of the time who were especially concerned by

references to Dagon throughout the text. It was finally published in a

duodecimo format after Hoag’s death by his granddaughter, Beverly Hoag Adams,

although prior to this several clandestine copies had been passed around amongst

occult circles. The first printed (or “Beverly”) edition is slightly abridged

and error-ridden due to cost constraints in its production. The original work

is still available for view however, in the Kester Library in Salem

Massachussets, USA. The most voluble proponent for the work was Harold Hadley

Copeland who cited the book extensively in his essay the Prehistoric Pacific

in Light of the Ponape Scriptures (1911) and who published his own

translation through the Miskatonic University Press in 1907.

The book deals

largely with the lost continent of Mu and the wizard-priest Zanthu who

doomed the place in a fiery cataclysm; it discusses Cthulhu, Idh-yaa

and their descendants including Ghatanothoa, Ythogtha, Zoth

Ommog and (obliquely) Cthylla. The text has dramatically affected

and informed the rites and practices of the Esoteric Order of Dagon,

among others.

(Source: Out

of the Ages, Lin Carter)

Hieratic

Naacal; author unknown; date unknown (discovered 1734); Sanity loss: 1d8/1d12;

Cthulhu Mythos +15 percentiles; average 20 weeks to study and comprehend

Spells: Contact

Deep One; Contact Father Dagon; Contact Mother Hydra; Contact Cthulhu

English;

Capt. Abner Exekiel Hoag; unpublished manuscript translation, various dates;

Sanity loss: 1d6/1d10; Cthulhu Mythos +10 percentiles; average 15 weeks to

study and comprehend

Spells: Contact

Deep One; Contact Father Dagon; Contact Mother Hydra

English:

“Beverly” edition; Capt. Abner Exekiel Hoag; 1795; Sanity loss: 1d3/1d6;

Cthulhu Mythos +5 percentiles; average 10 weeks to study and comprehend

Spells: None

English;

Harold Hadley Copeland trans.; Miskatonic University Press, 1907; Sanity loss:

1d4/1d8; Cthulhu Mythos +7 percentiles; average 12 weeks to study and

comprehend

Spells: Contact Deep One

“The Ponape Figurine”

In 1909, a diver discovered a

nineteen-inch tall, jade figurine of a grotesque creature from the seabed near

the island of Ponape. The carving was bought by the Sanbourne Institute of Pacific Studies where it came under the

scrutiny of Harold Hadley Copeland. Copeland’s examination of the piece was

meticulous and exacting as far as it went – positing the origin of the image as

Chinese and possibly deposited during the Chinese diaspora – but then it went right off the rails by once more citing

Angell and Thurston and even mentioning the Johansen

Narrative as a critical source. Even less welcome were his attempts to

prove that the figurine was a cult object connected with the Ponape Scriptures which he had just

finished translating the previous year, a work which had met considerable

disfavour amongst Christian and academic communities. The reception of this

article was cool at best and several colleagues suggested that Copeland take a

leave of absence.

English; Harold H. Copeland; 1910; 1d4/1d6 Sanity

loss; Cthulhu Mythos +4 percentiles; 7 weeks to study and comprehend

Spells: None

“Prehistoric Pacific in the Light of the Ponape

Scriptures”

Undeterred, Copeland returned to his

earlier work on myth patterns in the South Asian region and wrote a ‘compare

and contrast’ paper referring current Pacific mythography with the imagery

contained in the Ponape Scriptures.

The clear implication of the article was that there was an over-arching belief

structure that controlled and directed Oceanic and Southeast Asian cultures

from a shadowy background location, most likely based in China. Many academics

felt that Copeland was too busy buying into the fantastic paranoia of the

Angell-Thurston research and suggested that Copeland resign his post as the

head of the PAAA and a take a long

leave of absence.

English; Harold H. Copeland; 1911; 1d2/1d4 Sanity

loss; Cthulhu Mythos +2 percentiles; 7 weeks to study and comprehend

Spells: None

Zanthu Tablets

These

tablets were apparently given to Harold Hadley Copeland during the Copeland-Ellington

Expedition by a wizard called ‘Zanthu’, although it is unclear whether they

were handed to him by that entity or if he took them from Zanthu’s tomb.

Copeland was rescued in Mongolia after the expedition disappeared in 1923; he

was the sole survivor. When located, the ten tablets were in his backpack; they

are made of black jade and written all over in what Copeland described as

hieratic Naacal, the written language of Mu. The tablets now reside in the Sanbourne

Institute of Pacific Studies.

Hieratic Naacal; ‘Zanthu, Wizard of Mu’; prehuman

timeline; 1d6/1d10 Sanity loss; Cthulhu Mythos +6 percentiles; 60 weeks

to study and comprehend

Spells: Contact Deity: Cthulhu; Contact Deity: Ghatanathoa;

Contact Deity: Lloigornos; Contact Deity: Ubb; Contact Deity: Zoth-Ommog;

Enchant Bell

“The Zanthu Tablets: A Conjectural

Translation”

The text of

the ‘Tablets is most readily encountered in this monograph written by

Copeland just prior to his commitment to an asylum and suicide. There are no

spells in this translation; however their presence and function are alluded to.

There are claims that, in later years, more copies of the ‘Tablets have

been found by fisherman around the Pacific Rim.

(Source: Lin Carter, “The Dweller in the Tomb”)

English; Harold Hadley Copeland: The Zanthu

Tablets: A Conjectural Translation; 1926; 1d3/1d6 Sanity loss; Cthulhu

Mythos +3 percentiles; 8 weeks to study and comprehend

Spells: None