A common feature of HPL's stories (and those of his circle) is the presence of a brooding, precocious and often highly-strung creative type who inevitably dabbles with things Better-Left-Alone, leading to a dire conclusion. This archetype is not really that far-fetched: throughout history, writers and researchers have had a reputation for living fast and dying young. Sometimes being a slave to the muse has dire consequences leading to troubled lives and often grisly ends. Take this list, for example...

One of earliest authors to suffer for his art was the Roman poet Ovid (Publius Ovidius Naso: 20th March, 43 BC – 17 or 18 AD). A famous author of witty and often ribald poetry, his most famous works include the Metamorphoses - a retelling of Roman myths with a focus on magical transformations – and the Ars Amatoria, an ‘instructional’ and ironic cataloguing of the arts of love, followed by the Remedia Amoris, or lessons in the cures for passion.

In the year 8 AD, Ovid was banished to the village of Tomis on the Black Sea, for reasons which remain obscure, although Ovid himself describes his crime as “a poem and a mistake”. Augustus personally removed Ovid from the civilized world, bypassing examination by a Roman judge or a vote by the Senate. At the time, Augustus had imposed strict punishments for those indulging in polygamy in the Empire and it is thought that Ovid’s Ars Amatoria with its sly encouragement of adultery, was seen as seditious; the timing makes this scenario seem unlikely though. What is more likely is that this was just a pretext for punishment for an insult that has since been lost to time.

Ovid’s plummet from being the wealthy wit and social butterfly to becoming a dismal wreck, unable to even communicate with his barbarian neighbours, was cruel and unusual, and he died broken and alone.

Abelard (1079 – 21st April 1142) is perhaps best well known for his love affair with Heloise, the daughter of the French canon Fulbert, but his greatest contributions were in the area of scholastic philosophy and theology, including instructions in the use of logic. He became an opponent to the prevailing philosophy of Realism, combating it with his own brand of thinking, Conceptualism. Moving to Paris to teach, he became famous, winning philosophical duels and attracting an enormous body of students. Turning his hand to theology he again excelled, in time becoming the canon of Notre Dame Cathedral. It was only then that he discovered romance.

Contracted to instruct Heloise, the highly intelligent daughter of the canon Fulbert, Abelard fell passionately in love with his student and seduced her. Discovered by her father, Abelard was castrated as punishment, and forbidden to see her again. Nevertheless, he removed Heloise to a convent and convinced her – much against her will - to take the veil. Abelard was sent to a monastery where he continued to rail against the entrenched thinking of the times: one of his works - the Theologia ‘Summi Boni’ - was recognised as being heretical in its approach and he was made to personally burn all copies of it by way of penance.

His later life was plagued by attempts to punish him within the papal courts due to the fact that his ferocious intelligence and huge popularity as an educator were seen as threats to established dogma. He eventually died, tired and broken, at the priory of St. Marcel, near Chalon-sur-Saône; his reported last words were “I don’t know”.

Christopher Marlowe (c. 26th February 1564 – 30th May 1593) is a mystery wrapped in an enigma. A contemporary of Shakespeare and considered along with him one of the great tragedians of the English dramatic tradition, Marlowe’s works are dark and lurid, dealing as they do with death, horror and the occult. His "Massacre of Paris" is a short and dreadful retelling of the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre and features a silent character, an ‘English Agent’, whose presence is cited as a reference to Marlowe himself and his supposed clandestine activities during the incident as a spy. His play "The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus", departs from the legend in that Faust is dragged screaming off to hell at the end, there to be torn to pieces, whereas in the original German text, Faust burns his books and finds redemption before God.

Marlowe has been depicted as a rakehell, a brawler, a drinker and an atheist by many historians and authors, a character sketch derived mainly from court and parish records and various limited correspondence. His time at Cambridge was interrupted by extended periods of absence (longer than usually allowed by the institution) from which he returned with large quantities of money, which he spent lavishly. As well, he was once arrested for counterfeiting coins in Holland, in collaboration with Catholic agitators, a crime for which he was supposed to have been executed; instead, he was quietly returned to England and the matter dropped. It is these facts which have led many historians to conclude that Marlowe had connexions to the secret service of the time.

On the 18th of May 1593, a warrant was issued by the Privy Council for Marlowe’s arrest, although no reason was stated along with it. He appeared and was compelled to appear daily before the Council thereafter, until such time that they deemed his probation served. It is believed that the incident arose out of a manuscript containing “vile heretical conceipts [sic.]” that was obscurely linked to him. Ten days later, he was knifed to death at an inn at Deptford by Ingram Frizer, a con-man and bully-boy, also linked to espionage on behalf of the Royal Court.

James Hogg (1770 – 21st November 1835) started life as a Scots pauper, forced to labour on a distant relative’s farm, for which he became tagged with the pseudonym “The Shepherd Poet”. At the age of 14 he taught himself to read and write by borrowing books from his employer’s library: he learned to read Robert Burn’s poetry just in time to hear of the poet’s death, a fact that devastated him for the remainder of his life.

Moving to London he became a contributor to Blackwood’s Magazine and after some moderate success, became an outsider from the inner cabal of editors, often discovering his Scots’ style mocked and derided in print by his fellow contributors. His attempts at novels were increasingly poorly received, labelled as being maudlin and sentimental. In a final effort to write a worthy piece that would help support himself and his family, he penned The Private Memoirs & Confessions of a Justifed Sinner. The book did badly in terms of sales and Hogg died shortly thereafter.

In modern times, the work has been entirely re-evaluated: Andre Gide said of it, after having received it as a gift, "It is long since I can remember being so taken hold of, so voluptuously tormented by any book". Irvine Welsh, the author of Trainspotting, also cites it as a major influence on his style. The book explores the notion of Calvinism amongst the highland Scots and its plot weaves around the experiences of a young man who takes the teachings of his faith – that the Calvinist ‘Elect’ are born absolved from sin, regardless of the actions they take during their lives - to their ultimate and logically terrifying conclusion.

Thomas de Quincey (15th August 1785 – 8th December 1859) was born in Manchester of well-to-do parents although his father died when he was quite young; the family moved to Bath and his mother, a strict disciplinarian, pulled him from his upper-class school after three years, moving him to a lesser institution to prevent him getting an exaggerated opinion of himself. Academically advanced beyond his years, de Quincey was sent to Brasenose College in Oxford where he excelled but left abruptly before obtaining his degree.

He embarked upon a journey to meet William Wordsworth whose poetry had consoled him during fits of depression; but, too shy to fulfil this scheme, made his way instead to Chester, the home of Wordsworth’s mother, hoping to encounter one of the poet’s sisters. He was intercepted in this effort and returned to his relatives who agreed to a plan to let de Quincey embark upon a walking tour of Wales, on the proviso that he inform them on a weekly basis of his whereabouts in order that they could send him a weekly guinea to live on. Very early on, he forgot this condition and ended up in London begging for money. Discovered by accident by family friends and too ashamed to return home, he was sent to Worcester College in Oxford on a reduced income where he became known as a solitary and private individual. It was at this time that he began to take opium.

Failing to sit the exams that would have gained him his degree, de Quincey moved to the Lakes District and began translating German works in order to provide for his wife and children. It was at this time that he was convinced to write a serialised account of his opium addiction (Confessions of an English Opium Eater) and it became an instant success, initially serialised in the London Magazine but then soon released in book form. Around this time, he also came into his patrimony, a £2000 inheritance from his father, which he frittered away.

In the last decade of his life he lived in Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh – a sanctuary for debtors from which they could not be taken and gaoled. His mother’s death left him with £200 which his daughters managed for him and which allowed him to die relatively debt-free.

Lord Byron (22nd January 1788 – 19th April 1824) – to use the most recognizable of his many varied names – was the epitome of the Romantic hero, forging the archetype himself over his long and productive career. Borne of a family redolent with mad pirates, libertine wastrels and melancholy debutantes, he rose to become a scandalous figure in British society, famously described by Lady Carolyn Lamb as “mad, bad and dangerous to know”.

Dark-haired, saturnine and blessed with handsome good looks, Byron was at once a prey to his ruthless idealism as much as his rampant libido. Shortly after leaving university he travelled widely, attempting the Grand Tour – although the Napoleonic wars prevented him from seeing much of Western Europe. Instead, he travelled through the Mediterranean and the Ottoman Empire, experiences which fueled his taste for Orientalist invention and gothic themes.

His life as a member of the British peerage saw him as a dedicated defender of the Luddite movement in Parliament, a cause which inspired some of his most passionate political poetry; his career was curtailed however, by a need to return to Europe to avoid charges of incest and sodomy. His life there saw him learn Portuguese and Italian and travel extensively with other English literary exiles, most notably Leigh Hunt, Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife Mary Shelley. During his life Byron wrote copious poems and other longer works, including "Child Harold’s Pilgrimage", "The Corsair" and "Don Juan". Present at the beach cremation of Bysshe-Shelley after that poet’s drowning, a story became prevalent that he drank a farewell toast from his comrade’s skull, plucked from the flames; in actual fact he was disgusted and horrified by the cremation process and left to be quietly sick.

Byron spent his later life dedicated to the cause of Greece and her liberation from Ottoman rule. Using his own money he re-fitted the Greek fleet and set sail to Messelonghi. While organizing the impending attack upon the Turks, he caught a heavy cold which, unsuccessfully treated by bleeding, led to sepsis and his death from a violent fever. He is still remembered today as a great hero of the fight to liberate Greece and there are some who say that if he had lived he might have been crowned king of that country. A memorial to him in Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey was refused on ‘moral grounds’ and he was buried instead at the Church of St Mary Magdalene in Nottingham, although his heart (or perhaps his lungs – no-one is sure) was buried at Messelonghi in response to an appeal from the Greeks. A memorial to him was erected in Westminster Abbey at last in 1969, 145 years after his death.

If Byron was the archetypical Romantic Poet, there were many who tried to emulate him and even surpass him in his achievements – or at least his dramatic take on life. One such was Thomas Lovell Beddoes (20th July 1803 – 26th January 1849), son of a famous surgeon who was a friend of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. The younger Beddoes was educated at Charterhouse and Pembroke College, Oxford, and, in 1821, published a book – The Improvisatore – which he later tried desperately to suppress. He followed this with "The Bride’s Tragedy" (1822) a blank verse play that was well received. These were the only works of his which were published during his lifetime.

His later life was spent furthering his education by training in medicine. Following his morbid pre-occupation with death, he sought through his studies to discover that element of the human spirit which survives physical death. He was expelled from the University at Göttingen and went to Würzburg to complete his studies. During this time he became involved in radical politics and was apprehended and deported from Bavaria and again from Zurich, to which he had re-located.

He became largely itinerant after this period, returning to England in 1846 for a short time before escaping back to Germany. His demeanour during this period became highly erratic and increasingly gloomy, a leg injury causing the limb to be removed below the knee. He finally moved to Basel in Switzerland where, in 1849, he committed suicide by injecting himself with curare. His major opus, a blank verse play entitled "Death’s Jest Book", was published posthumously.

Of all the writers on this list, Emily Dickinson (10th December, 1830 – 15th May, 1886) can likely be said to be the least self-destructive. A New England spinster, she grew up in a strict but loving household and became posthumously, one of America’s pre-eminent poets. She was increasingly bitter throughout her life at the prospect of having to care for her infirm mother, feeling that this duty robbed her of any chance to pursue her own ambitions. Nevertheless, she wrote copiously and engaged in extensive correspondence with friends, family and publishers. As she grew older she became increasingly more reclusive and took to dressing only in white clothing; eventually she would only talk to guests from behind doors or curtains, although she was still known to be effusively welcoming and generous to these visitors.

Her poetry was badly misunderstood during her lifetime and she only ever saw around seven of her poems, albeit horribly mangled by editors, make it into print. She was largely dismissed as a weak poet with a poor grasp of grammar by contemporary publishers, although time has shown that she wrote with a diamond-bright precision, capturing a multitude of fleeting and ambiguous emotions with her deceptively light styling. She was known to refer to writing as the path to immortality and she became morbidly obsessed with notions of death and dying. She died of Bright’s Disease only a few years after her mother and, according to her instructions, her white coffin was carried to its resting place through a field of buttercups, bedecked with white and blue flowers.

Where to start with Oscar Wilde (16th October, 1854 – 30th November, 1900)? He was born in Ireland to intellectual parents and proved early on that he was precociously intelligent and ambitious. He studied Classics at Dublin and Oxford Universities then moved to London to pursue his ideas of the Aesthetic Movement which had been instilled in him by the likes of John Ruskin, among others. He soon became a notable social figure, known for his rapier wit, sparkling conversation and pithy epigrams. He wrote poetry and worked as a journalist before touring America and Canada to lecture on Aestheticism. During this period he wrote his only novel – The Picture of Dorian Gray – and wrote the play "Salome" in French whilst in Paris: its subject matter caused it to be refused license by the authorities and it was never performed during his lifetime.

Undeterred, Wilde set off to England once more and wrote a series of society comedies, amongst them "The Importance of Being Ernest", which secured his place as the leading dramatist and playwright of his era. Unfortunately, at the height of his success, he sued the father of his lover for libel and lost the case in court, being gaoled for two years with hard labour for the crime of “gross indecency” with another man. Upon his release, he left Britain for Paris, never to return. Before dying penniless in that city, he penned his last work, a long poem entitled “The Ballad of Reading Gaol” which explores the rigours and insights which he encountered whilst in prison.

Virginia Woolf (25th January 1882 – 28th March 1941) was born into a family of prestigious literary and artistic connexions with links to the best of Victorian artistry. Her parents had both been married previously and had children from those families so there were children of three pairings under the same roof. Virginia’s half-brothers were sent away to a formal education while she and her sister Vanessa were educated from home. During her early life, between trips to Cornwall and bouts of modelling for various Pre-Raphaelite painters such as Edward Burne-Jones, Virginia and her sister suffered continuous sexual abuse from their half-brothers and this took a toll on her peace of mind and eventually her sanity.

After graduating from the Ladies’ Department of King’s College London, Virginia moved to the suburb of Bloomsbury and the roots of The Bloomsbury Group were established. Along with many other young writers and intellectuals, Virginia began writing and publishing, marrying her husband Leonard Woolf along the way. Together they set up the Hogarth Press and began to publish many avant-garde works including those by T. S. Eliot and Laurens van der Post, not least Virginia’s own novels and other works. Given the Group’s disdain of sexual exclusivity, Virginia began an affair with another woman, Vita Sackville-West, which continued through most of the 1920s; at the end of the affair, Virginia wrote her novel Orlando in dedication to her lover.

Throughout her life, Virginia was stricken with severe bouts of depression which prevented her periodically from working. With the onset of World War II, the destruction of her house during the Blitz and the knowledge that she and her Jewish husband had been specifically targeted by Hitler, she fell into a black despair which she terminated by filling the pockets of her overcoat with stones and walking into the River Ouse. Her body was recovered twenty days later.

Born in Kiev from a line of priests, Mikhail Bulgarkov (15th May 1891 – 10th March 1940) is perhaps the most famous of modern Russian writers, through the simple expedient of having his magnum opus unpublished for over twenty years. Bulgarkov graduated from the First Kiev Gymnasium where he developed a passion for Russian and European literature. He enlisted with the Red Cross as a medic during the First World War and was sent to the front, where he was seriously wounded on at least two occasions, leaving him afflicted by chronic pain for the rest of his life. During the Russian Civil War, he and his brothers sided with the White Army and fought for the Czar: eventually he fled with his family to the Caucasus from where his brothers were invited to return to Paris as doctors; Bulgarkov himself was barred from emigrating as he had contracted typhus during the wait. He never saw his family again.

Returning to Kiev, he began his writing career in earnest completing several short novels inspired by H. G. Wells and his own experiences in battling morphine addiction to quell his chronic abdominal pain. He then moved to Moscow and continued to work as writer; however many of his pieces attracted a severe mauling from the critics on the basis that he was “too anti-Soviet”. His material was banned and by 1929 his career was in ruins.

Marrying for the third time in 1932 to his muse, Yelena Shilovskaya, he began to secretly write his greatest novel, The Master and Margarita. Continuing to find no support for his writing efforts, he wrote a play entitled “Batum” which praised Stalin effusively; Stalin himself banned this work but, remembering an earlier play of Bulgarkov’s which he had seen and enjoyed, he found a position for the embattled writer at the Moscow Art Theatre. Denied the ability to freely express himself even here, he wrote to Stalin in despair asking that he be allowed to emigrate from Russia if no work could be found for him; Stalin rang him personally to ask if indeed he wanted to leave Mother Russia, to which Bulgarkov replied (inevitably) that a Russian writer cannot live outside of his homeland.

Bulgarkov died of Bright’s Disease in 1940, leaving his greatest work completed behind him, in secret. It was finally published in 1967 and has since been recognised as one of the greatest works of literature of all time.

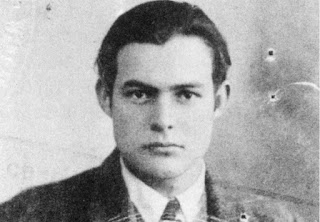

Ernest Miller Hemingway (21st July 1899 – 2nd July 1961) led a life of incredible bravery and harshness and committed as much of it as he could to paper in his spare, sparse prose. In his teens he enlisted as an ambulance driver on the Italian front during the First World War and witnessed scenes of incredible carnage, including an explosion amongst female workers in a munitions factory of which he wrote "I remember that after we searched quite thoroughly for the complete dead we collected fragments". For his efforts in this War he received the Italian Silver Medal of Bravery.

Returning to America, Hemingway became attached to the Toronto Star as a freelance writer and moved around Canada and the US. In Chicago, he met his future wife Hadley Richardson and, soon after they married, they went to Europe to join the “Lost Generation” of writers in Paris. Hemingway became acquainted with James Joyce with whom he embarked upon some legendary drinking sprees. Travelling around Spain and France, Hemingway produced a large quantity of manuscripts which he intended to get published; however Hadley lost the suitcase that they were in at the Gare de Lyon, and they were never recovered. A small work, Three Stories & Ten Poems, was all that could be restored and printed from the missing manuscripts.

Hemingway and Hadley returned briefly to the US for the birth of their son before returning to Spain where Hemingway determined to write a novel. During the writing of The Sun Also Rises, he began an affair with a woman named Pauline Pfeiffer and this led to his divorce from Hadley, upon whom he settled all of the proceeds of his forthcoming book. After this, he moved to Key West, wrote A Farewell to Arms and began a period of wintering in the Caribbean and spending the summer months in Wyoming. During this time he travelled to Africa writing many short stories and other tales (“The Snows of Kilimanjaro”) derived from his experiences there. He also wrote To Have & Have Not, the only novel he wrote during the 30s.

In 1937, Hemingway travelled to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War. There he met and fell in love with Martha Gellhorn. 1939 found him living in Cuba and writing For Whom the Bell Tolls as part of his acrimonious split from Pfeiffer. He married Gellhorn and the two of them went to China to further Gellhorn’s career as a journalist. Finding China not to his taste, Hemingway left Gellhorn and flew to Europe where he intended to cover the Battle of the Bulge. Unfortunately he contracted pneumonia and missed most of the action; upon his reunion with Gellhorn in London, she declared herself “over him” and left. He was awarded the Bronze Star for Bravery during the conflict and, while being interviewed by Time Magazine about his wartime efforts, he became infatuated with the reporter, Mary Welsh and they married soon after.

Hemingway was later involved in a series of accidents, the injuries of which were never fully diagnosed and the resultant chronic pain brought his incipient alcoholism to full fruition. Struggling to finish The Old Man & the Sea, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, but was never able to finish any of the many projects upon which he subsequently embarked. Increasingly paranoid at the end of his life, Hemingway believed that the FBI was secretly investigating him. Declining health and failing eyesight saw him confined to the Mayo Clinic where he was subjected to electro-convulsive therapy as many as 15 times in 1960. Upon his release, he returned to his home in Idaho and blew his head off with his favourite shotgun in the front foyer of his house, leaving only his lower cheeks, mouth and chin intact.

Born Anne Gray Harvey in Newton MA., Anne Sexton (9th November 1928 – 4th October 1974) was afflicted by mental illness for most of her life. Due to controversies and speculation surrounding her psychological treatment, the exact nature of her disability is unknown but it has been suggested that she was either schizophrenic or manic-depressive. To combat her periodic episodes of mania, she was convinced to undertake courses in poetry writing and soon proved to have a natural talent for the process. Her work is classified as being “confessional” in nature, dealing as it does with the various issues surrounding her life and mental issues. In 1967, she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for poetry.

Married in 1948 she developed many issues surrounding her role as a wife, mother and a woman in society. Her work concentrates on such themes as depression, isolation, despair, menstruation, abortion and adultery; strikingly so in a period where these topics were routinely repressed and ignored. She wrote a play entitled “Mercy Street” which won critical acclaim in 1969 and even performed with jazz musicians in her own group entitled Her Kind. She rose to become the most awarded poet of her day, with not only the Pulitzer behind her but also membership to the Royal Society of Literature and the Harvard chapter of Phi Kappa Beta.

But it was not to last. Increasing dependence on alcohol and a change of therapist (who some say encouraged her into an inappropriate affair with him) pushed her already fragile sensibilities to the tipping point: after submitting the final draft of her next book of poems, The Awful Rowing Toward God, she went home, poured herself a large glass of vodka and went to sit in her running car in the garage while she quietly went to sleep.

Born to Austrian immigrants to America, Sylvia Plath (27th October, 1932 – 11th February, 1963) was profoundly influenced by her father in her early years, a combination of his being so much older than his wife (a 21-year gap), his strictness despite his own rebellion against his parents and his bizarre death: convinced he had contracted lung cancer, he refused to seek medical aid and thus died of the diabetes he developed untreated, due to complications surrounding the amputation of his foot. Sylvia’s artistic talents were noticed early on and she won junior art prizes and had poems published in the local newspapers.

She attended Smith College in Massachusetts and enjoyed her time there, despite breaking her leg during a holiday while skiing. After her third year she won a month-long internship at Mademoiselle Magazine in New York, but found the experience to be disillusioning. It is from this time that an inevitable downward spiral into despair can be traced. Upon returning from New York she crawled beneath a house with a bottle of sleeping pills and tried to commit suicide, her first attempt. Revived, she was committed to a mental asylum and nursed back to health with a treatment involving electro-convulsive therapy (ECT). Thereafter, she submitted her thesis, thereby graduating from Smith, obtained a Fulbright Scholarship to Cambridge and went to live in England.

Leaving Cambridge in 1954, she travelled to and from the university to keep in touch with friends. During one of these visits, she met Ted Hughes and shortly afterwards they were married. They spent the next few years bouncing between Britain and America, during which time they had two children and Sylvia published her semi-autobiographical novel, The Bell Jar. In 1962, after trying to kill herself again by crashing her car, she discovered that Hughes had been having an affair and they separated. Sylvia moved back to London with the two children and embarked upon the most productive year of her life, during which the majority of her best poems were produced. In February the following year, after enduring England’s coldest winter in a century, she finally succeeded in committing suicide by gassing herself to death with the kitchen oven.

Half Irish-American, half Creole, John Kennedy Toole (17th December, 1937 – 26th March, 1969) was born in New Orleans to a retiring father and a controlling, domineering mother. His early life was thoroughly planned by his mother and she occupied his free time with amateur dramatics and music, even winning their troupe a program on local radio. Toole was academically gifted and decided to focus his efforts on his study: he left the entertainment world and became a noted toastmaster and debater. During his school life he won a National Merit Scholarship was named to the National Honour Society and won a scholarship to Tulane University by the time he was 17. In his last year of high school he wrote his first novel, The Neon Bible, an effort which he conceded was flawed but which he submitted for publication regardless; it was turned down and did not see print until after his death.

Throughout his academic career, Toole was universally regarded as a sparkling wit with dead-pan delivery; he was always considered to be the life of the party. At Tulane he worked on the campus newspaper, the Hullabaloo, writing articles and drawing cartoons. In his spare time he travelled in New Orleans’ French Quarter or the Irish Channel, parts of the city of which his parents – especially his mother – heartily disapproved. Graduating with honours from Tulane in 1958, he went to Columbia University on a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship where he completed his masters’ degree in one year. He then returned to Louisiana to teach English at the University of Southwestern Louisiana. Many of his friends noticed that he became withdrawn and sullen whenever his mother came to visit and he started to pursue odd obsessions for country music and Marilyn Monroe (after whose death he became severely depressed). He accepted a teaching position at Hunter College at the University of Columbia which suited his desire to study his post-doctoral thesis there.

In 1961, he was drafted into the Army and spend many years in Puerto Rico teaching English to the locals. Army life bored and depressed him and he began to drink heavily while angling for the only benefit to be gained from his military position there – a private office. Having secured this trophy, he began writing his great novel, A Confederacy of Dunces. He stayed in Puerto Rico until 1963 when the economic privations of his family gained him a hardship discharge to return home. He took a teaching position at the Dominican College, an all-girl school where he taught English. Becoming an instant hit with his students as well as the staff, his classes were always popular and packed. The assassination of John F. Kennedy in November of that year sent him into a black depression during which he stopped writing and began to drink heavily.

The completion of his novel, an event which should have brought much pleasure, only began a series of badgering encounters with his mother who demanded that Toole persevere in getting it published. She pushed him into meetings with publishers during which he felt that he’d embarrassed himself and he finally tossed the manuscript on top of a cupboard to be forgotten. As a result of all of this, his behaviour became erratic: he exhibited strong paranoia and suspicion of others and would explode in raging tirades against the Church or the Government during his lectures. In a final blazing row with his mother he left home, taking his clothes and the contents of his bank account with him. His whereabouts became a mystery.

It transpired that he had driven to California to visit the Hearst Family Mansion and had then driven to Milledgeville, Georgia, where he had tried to visit the home of deceased writer Flannery O’Connor, whose works he had admired. Finally, he drove to Biloxi, Mississippi, where he rigged a hose to the car’s exhaust pipe and gassed himself to death. His suicide note was handed to his parents but his mother destroyed it after reading its contents and refused to divulge the message it contained. She took his manuscript and, using the very bullish qualities of which Toole had despaired, eventually succeeded in getting A Confederacy of Dunces published in 1980, to international acclaim and 1981’s Pulitzer Prize for literature.

Kurt Cobain (20th February 1967 – 5th April, 1994) was born in Aberdeen, Washington State, and, with his band Nirvana, became the reluctant voice of his generation. At the age of eight, his parents split and this caused an irreparable change to his personality, scarring him deeply for the rest of his life. The resentment he felt as a result of this act informed the rest of his childhood and adolescence: he became rebellious and anti-authoritarian, indulging in acts of vandalism and finding ways to deliberately disappoint his parents. Failing to earn enough credits to graduate from high school, his mother told him to get a job or leave home: finding all of his effects packed up and stored away, he began to stay with friends or sneak into his mother’s house after dark to sleep. He claimed to have even lived rough beneath a bridge in the nearby woods.

Forming the band Nirvana in 1985, he wrote and released their first album “Bleach” which held many references to his failed and dysfunctional relationship with Bikini Kill musician, Tobi Vail. Replacing the band’s drummer with new performer Dave Grohl, the band embarked upon their second album “Nevermind” in which Cobain finally began to deal with the demons of his early years.

Cobain suffered all his life from an undiagnosed chronic stomach disorder which caused him great distress. The pain of this was compounded by poor self-image leading to eating disorders and malnourishment. He attempted to control the bouts of pain with the novel approach of becoming a heroin addict which, he claimed, was the only way to alleviate the suffering. No stranger to drugs, Cobain’s indulgence was exacerbated by his meeting, and marriage to, Courtney Love, whose brash personality threatened to obliterate him completely. He began to obsess about joining the mythical “27-Club”, an unofficial grouping of musicians all of whom had died after turning 27 and which includes Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin among others. In 1994, after taking all the drugs and completing Nirvana’s third album “In Utero”, he escaped rehab, dodged pursuit and returned home, ending his life by means of a shotgun blast to the head. At 27 years of age.