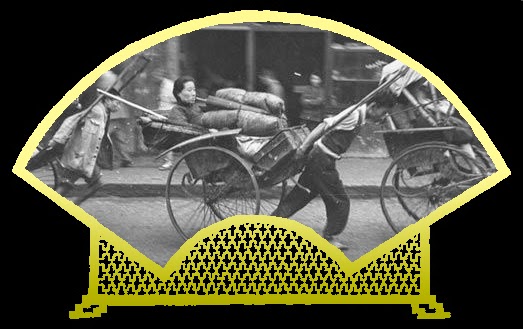

The rickshaw was not invented by the

Chinese; in the early days of the Settlement, its place in the public transport

scheme of Shanghai was occupied by the barrow. Travelling by barrow was bumpy

(due to a lack of suspension technology), often crowded (riders were usually

forced to double up or to share with other deliveries) and heavy work for the

person doing the pushing. The first rickshaws were brought from Japan by an

innovative Westerner, a French merchant named Menard, who had seen how

successful they had been in that country. In Shanghai, they were formally known

as ‘jinrickshas’ a Japanese word

which means ‘man power vehicle’; the everyday Shanghainese however rarely used

this term, preferring the word ‘dongyangche’

or ‘Japanese vehicle’. By 1913, the Municipal Council had passed regulations

stating that all public rickshaws be painted yellow to distinguish them from

private rickshaws; from this time they were usually called ‘huang baoche’ or ‘yellow private vehicle’ by the Shanghai Chinese

residents.

Menard had approached the French

Concession council in 1873 with a plan to gain a patent license to run “hand

pulled vehicles” in the Concession for a period of ten years; the French

Council took the proposal to the International Council and together they chose

a different idea: they would allow 1,000 rickshaws to run in the two

settlements (500 in each) and would issue twenty licenses each, with permits to

run 25 rickshaws. As a courtesy, Menard was offered 12 of the licenses for the French

Concession for a total of 300 rickshaws. By 1874, there were ten rickshaw

companies run by foreign investors running the 1,000 rickshaws.

Like most industries in Shanghai, the

companies set up by wealthy, white taipans

were left (for some considerable interest) in the hands of capable compradors; these, in their turn passed

on the wearying details of running a daily business to go-betweens (again, for

a lucrative return) and the structures of these fragmented businesses became

extremely frayed and hard to trace. When – inevitably – more licenses were

issued by both Councils, the existing companies were quick to snap them up and

rent them out to new, eager managers. Ownership of a license was signified by

the expedient of an enamelled badge which was required to be affixed to the

rickshaw in question.

The Councils of the foreign communities

were traditionally inimical to the movement of human-powered traffic on

Shanghai’s streets. The barrows of the hard-working barrowmen were marginalised

in new traffic regulations aimed at freeing up space on the city’s streets:

concubines deprived of this useful means of transport were often seen perched

upon chairs strapped to the backs of coolies en route to their various assignations. The rickshaws became a

happy medium between the two extremes and due to the fact that they were cheap,

fast and could access areas of the city unable to accommodate cars, buses, or

trams, were an instant hit. Working as a rickshaw-puller became a viable

alternative to the shameful occupation of a coolie and many men from the farms

in the districts outlying Shanghai flooded in to try their hands.

Well-meaning missionaries objected to

what they saw as back-breaking labour inflicted upon the poor and homeless:

inevitably, during Shanghai’s history, movements were launched to curtail or

regulate the industry for the sake of the workers and their health but, as in

so many instances, the outraged parties were victims of their own flawed

perceptions. Pushing a barrow is a combination of lifting and pushing, where

the weight of the load is supported between the front wheel and the arms and

back of the barrowman; in contrast, a rickshaw and its load rests on its own

wheels while the rickshaw-puller only provides momentum, directional control

and a counterbalancing weight. It is a much simpler process and relatively easy

on the operator. If a rickshaw-puller acted in distress to cadge an extra tip

from a soft-hearted –often foreign - client, it was not usually a realistic

comment on conditions.

In fact, many operators held two or more

jobs. Rickshaw companies would assign vehicles to a roving throng of willing

applicants over three shifts on a daily basis: pulling shifts were assigned on

a ‘first-come, first served’ basis and there was no need to maintain a fixed

stable of rickshaw-pullers. A worker may have had a lucky streak of several

shifts’ work and as equally could attract several days of unemployment. As a

result, many rickshaw pullers split their time between fixed-rate employment as

factory workers (seen generally as dangerous and uncomfortable), labouring

coolies (degrading and laborious) or rickshaw-pulling (relatively easy and with

opportunities to earn bonus tips and other gratuities). Many older

rickshaw-pullers often worked only the odd shift now and then, to provide

pocket-money into their sixties and seventies. The difficulty was not so much

the work (which was by no means easy) but in learning the tricks to maximise

income.

The rickshaw-puller’s dream was to become

the puller of a private rickshaw. This meant being placed on a retainer and

being given the care of a privately-licensed vehicle attached to a company or

wealthy household. Compradors, their taipans and other wealthy foreigners

were often on the lookout for rickshaw-pullers who seemed to be a ‘cut above’,

able to work quickly, with tact and sensitivity and with a pleasant outlook.

These happy types would balance the downside of being always on call, with the

relative ease of a regular pay packet and often accommodation near the garage

or stable. And if they managed occasionally to rent out the rickshaw to others,

their masters never needed to know.

Because the rickshaw men travelled widely

across the city and were often called upon to wait for their clients for long

periods at their destinations before returning them home, they were privy to

much street-level information that they could parlay into extra wealth. Canny

rickshaw-pullers kept their ears to the ground and quickly learned to put two

and two together: an extra tip to the rickshaw man could ensure that the

details of a midnight assignation would never make it to the ‘Mosquito Press’.

No comments:

Post a Comment