“...The chief virtue of

their strategy is extreme caution and love of craft, not without a large share

of perfidy and falsehood.”

-John Davis, c.1830

The blasted Plateau of Leng intersects

the Waking World at two points close to China: the Plateau of Sung in Burma and

the Plateau of Tsang in Tibet. The Tcho-tcho diaspora from these cursed locations inevitably draws them to

Shanghai where they hide as lower caste workers and pedlars of strange

knowledge, often connected to the Triads. The rising death rate in the city has

also seen the emergence of several restaurants specialising in ‘chaucha cuisine’...

The nature of the Tcho-tcho is to be

secretive and coercive: they are never overt in their machinations but tend to

play hidden hands. A Tcho-tcho would rather hold a background position in any

organisation and subtly manipulate from the shadows that such cover provides;

it is not in their nature to hog the limelight or become figureheads. The

Tcho-tcho always regard leaders as puppets, limbs that can be sacrificed if

things become desperate.

At all times the Tcho-tcho craves power

and acquisition. For this reason, they gravitate towards the secret societies

of China – the Triads, the Tongs and chiu-chee

Brotherhoods – steering them discreetly towards the nefarious ends of their

hidden masters. The trail of the Tcho-tcho diaspora

from the mountainous west can be tracked by the outbreaks of rebellions and

other instances of civil unrest from the Muslim

Uprisings in Yunnan, the Taiping

Rebellion, the Chinese Revolts of

1865, the Tientsin Massacre

through to the Boxer Rebellion. In

all these instances the hand of the insidious Tcho-tcho can be seen.

The Tcho-tcho are ostensibly loyal to their

chosen deity, the twin abomination Zhar and Lloigor; however, these loyalties

are notoriously fluid and are dispensed with at need. Many Tcho-tcho work

diligently for the Brotherhood of the White Peacock, the Hsi Fan and its monstrous god the Emerald Lama; their involvement

is almost certainly coerced and rigorously (and ruthlessly) policed. The only

being that a Tcho-tcho is really happy to work for is itself and its own

personal agendas.

The Tcho-tcho are not brave. Their lust

for power is never greater than their sense of self-preservation: they will

gladly cede the battle in order to win the war. Their memories are long

however, and a setback to their schemes will not be forgotten - or forgiven -

easily.

The

Margary Affair

Augustus Raymond Margary was a junior

British diplomat who was sent from Shanghai to discover an overland route

across China to British India. The plan was that he was to travel by foot,

horse and boat to Bhamo in British-controlled Burma with his personal staff,

there to meet with a Colonel Horace Browne. Margary was a sickly and not

particularly diligent traveller and his trip was protracted and slow. He

suffered from bouts of toothache, pleurisy, rheumatism and dysentery while

traversing the length of the Yangtsze and these illnesses slowed him down

considerably.

Margary was an amateur botanist and

linguist by vocation. He failed his examination to enter the diplomatic corps

three times before finally succeeding and served as a translator in Peking,

Formosa, Shanghai and Yantai. A dreamy and introspective individual, in

hindsight he was probably not the most fortunate choice for this particular

mission.

Following a route to the headwaters of

the Yangtzse, Margary took an unprecedented six months to make the 1800-mile

journey through Szechwan, Kweichow and Yunnan, finally meeting up with Browne

in the Burmese town of Bhamo in late 1874. In preparing for the return journey

in early 1875, Margary suddenly abandoned his proposed return route and instead

diverted his team to the town of Tengyue in southern Yunnan.

Arriving at Tengyue, Margary made

surprising arrangements for an extended stay. Soon afterwards, he was taken by

local guides to visit a series of caves and, after being separated from his

staff, was brutally murdered. His staff was killed shortly thereafter and all

the bodies disposed of.

Rumour of the incident reached Colonel

Horace Browne shortly afterwards. Setting off in pursuit of Margary’s team, he

established an investigation to determine what had happened to the diplomat and

his staff. After several weeks of searching and interrogating the locals,

Browne was able to compile a report of the incident along with such evidence as

he could put together to account for Margary’s disappearance. This material was

sent back to the British Legation in Peking.

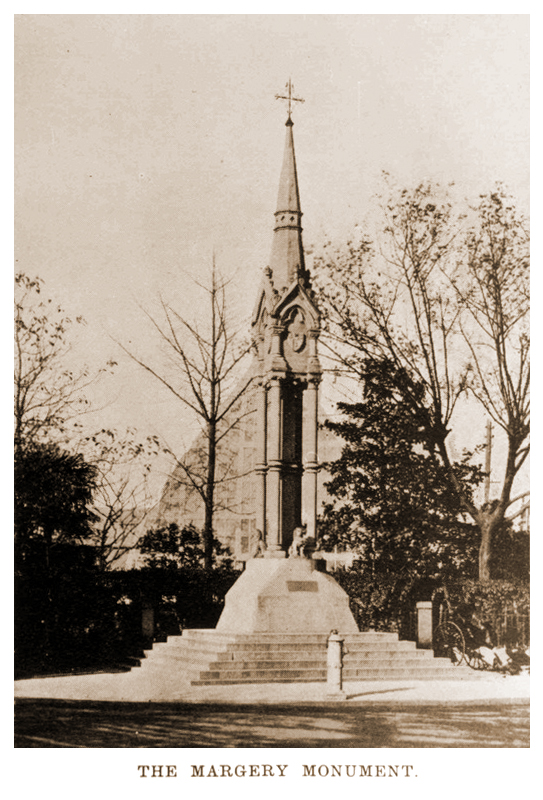

Britain at once sued for reparation

against the Chinese Imperial Government. A tense process of negotiations was

embarked upon which was not concluded until 1876, with the ratification of the Chefoo Convention. This amounted to 700,000

taels of silver as compensation for Margary’s death, a mission of apology from

the Dowager Empress to Queen Victoria, the erection of a memorial in Shanghai

in Margary’s name and the opening of four more treaty ports in China. The tone

of this treaty, conducted by Thomas Francis Wade and Li Hung-chang, extended

much beyond the simple facts of a Briton’s death at the hands of Chinese

nationals and embraced a much wider rising tide of anti-foreign sentiment that

was sweeping China at the time.

The official report of Margary’s death

claims that he diverted to Tengyue on the strength of rumours of bandit activity along his chosen

route; Browne’s original notes however, indicate that Margary had decided to

strike off in that direction in search of a ‘revelation’ that local natives had

told him about. It’s possible that the official report neglected to include

this information in order to strengthen the case against the Chinese

government. Browne found many of Margary’s personal belongings distributed amongst

the natives of Tengyue, including Margary’s Journal:

after despatching them to Peking, these effects were sent on to Shanghai for

return to his family in Britain. Inexplicably, the parcel was stolen en route and considered lost.

That might have been the end of the story

except for the fact that the Journal

reappeared mysteriously. It showed up at an auction in Cefalù, Italy, and was

purchased as part of a bundle of old books and papers by the archive of the

University of Zurich. In later years a certain Prof. Hinterstoisser came across

it whilst writing his theory of magical practise, and included it in his

researches. It is not clearly understood what relevance to Hinterstoisser’s

work the Journal had, but then the

book was later presumed to have been lost in a fire that consumed the

Professor’s offices at the University and which destroyed all of his notes. The

Professor’s work - Prolegomena zu Einer

Geschichte der Magi – was destroyed by the Nazis before being released and

no known copy exists to enlighten the issue. Professor Hinterstoisser

considered (or was convinced) that the effort of reconstructing the work was

too onerous to embark upon and he turned to other things.

From what little is known about the

incident and the cause of Margary’s death, it can be assumed that Margary was

led astray by the promise of being shown something incredible, something which

would take him some time to analyse (given the fact that he made plans for an

extended stay at Tengyue in Yunnan). This isn’t the first time that such an

incident has occurred, given the existence of the Thirteenth Century scroll,

The Abduction of the Mandarin Hsu, which details the Tcho-tcho performing the

same routine that they carried out with Margary. The fact that Hinterstoisser

alluded to the document in his magnum opus confirms that, whatever was promised

to Mandarin Hsu and Raymond Margary, it fell under the heading of ‘magic’.

Further, the fact that the Nazis tried to eliminate all record of

Hinterstoisser’s work shows that they had knowledge of it and were concerned

enough about it to keep it hidden from other explorers.

Whether this thing is a force for good or

completely malevolent remains to be seen. The implication is however, that

there is something powerful to be discovered in the mountainous terrain of

western China...

*****

This is really for the Keeper to decide

as they see fit for their own campaign. The following two options are presented

for review, however there are other possibilities.

The

Black Lotus Revealed: Given

Margary’s predilection for strange flowers, this is an obvious option.

Tcho-tcho individuals let slip to the diplomat the whereabouts of the sacred

plant and lured Margary astray; when elders within the Tcho-tcho ranks learned

what was going on they ordered Margary’s execution as well as that of his

staff. The journal kept by the diplomat was not thought of by the cannibals

until afterwards and they struggled to prevent it falling into the hands of the

authorities with limited success. Now the Nazis covet the vile weed, seeing in

its propagation a means of combating the ‘racially impure’ with a range of

insidious weapons from the Liao Drug to the Flower of Silence.

The

Great White Space: What

Margary was led to was the gateway to Croth and beyond it the hidden

dimensional portal that allows the Old Ones to travel across trillions of miles

of space. A covert expedition in 1933 tried and failed to access this site

alerting the Ahnenerbe of its possibilities: they tracked down copies of the Ethics

of Ygor and the Trone Tables, eventually locating the Margary Journal and

preventing Hinterstoisser’s publication of its secrets. The Nazis are now keen

to control the dimensional rift and turn it to their own ends: their uneasy

truce with the Japanese in Shanghai will last only long enough for them to find

the lost city of Croth and access The Great White Space.

*****

Prolegomena

zu Einer Geschichte der Magie (‘Preliminary Remarks on the History of Magic’)

A problematic text. Shortly before being

released, the entire print-run of this work was seized and destroyed by the

Nazis. However, the standing type was left intact and it is presumed that a

handful of copies, maybe as few as one or two, were quickly printed and hurried

out of Europe. Hinterstoisser’s notes, drafts and galley-proofs were all

destroyed in a mysterious fire thus preventing him from resurrecting the work

after the War. Little is known of the book’s history apart from a reference to

it being sought by covert US forces at the end of World War Two; many believe however that certain passages shed

light on the Margary Affair of the

previous century.

(Source: Necronomicon: the Book of Dead Names, George Hay, Ed.)

German; Dr Stanislaus Hinterstoisser;

1943; No Sanity loss; Occult +8

percentiles

Spells: None

The Margary Journal

Augustus Raymond Margary was the touchpaper who lit

off an explosion of violence against the Chinese: his murder, in tandem with

the Tientsin Massacre of the missionaries there, caused a major outcry

against the Manchu courts by an, unusually unified, world court. Hundreds of

thousands of taels were paid to Britain in compensation for this death

and the Dowager Empress was forced to send an apologetic emissary to Queen

Victoria’s court. All this for a whiney, upper-class milksop with a flower

fetish.

In the end, Margary was just an excuse to let the

Foreign Legations put some stick about and remind the fractious Ching dynasty

who was boss. After the Chefoo Convention and the raising of a trite

little obelisk to his memory in a remote corner of Whangpu Park in Shanghai,

Augustus Margary was forgotten by pretty much everybody. Everybody that is, who

hadn’t had a look in his Journal...

Colonel Browne’s report on the murder officially

stated that Margary had been ambushed by bandits while attempting to return to

Shanghai; his personal notes and report state otherwise: Margary had detoured

from his route and followed some local guides to a remote location where he had

been set upon and killed. His attackers having almost certainly been

Tcho-tchos, he was probably still alive when they started feasting...

What, if anything, was recounted in the Journal,

has vanished into the ether and that’s probably just how the Mythos powers that

be like it. Margary kept an official Account of his travels that was

edited and published posthumously by Sir Rutherford Alcock, and the existence

of this volume has tended to muddy the waters in substantiating Col. Browne’s

account of the incident. Diligent readers should try to keep the two books

separate in their discussions and investigations.

English;

Augustus Raymond Margary; 1874-1875; 1d2/1d6 Sanity Loss; Cthulhu Mythos

+4 percentiles

Spells: None

English; Sir Rutherford

Alcock, KCB; 1876; 0/0 Sanity Loss; Cthulhu Mythos +0

No comments:

Post a Comment