Last

Friday I went down to Sydney to see the current exhibition on the life of

Alexander the Great at the Australian Museum. I hadn’t actually heard that this

was showing, living out in the boondocks as I do, but any excuse to go and

sniff around the institution that holds the Cthulhu idol taken from the SS. Alert will do me (seriously, it’s

right there in “The Call of Cthulhu”,

although the place is no longer called the “Sydney Museum”).

An

early start and two hours on the train saw me on the steps of the Museum

waiting for the rest of my party to arrive. An encounter with a particularly

officious and over-zealous volunteer put me in a bad mood that wasn’t going to

get any better without caffeine so, being barred from entering the Museum Cafe

(despite signs clearly stating that I could come and go from there as I chose)

I mooched around the corner to Stanley Street and sank a scalding long black to

get my head straight. Back at the Museum, my friends had beaten the volunteer

into a retreat and we were finally allowed access.

In

the past, exhibitions at this place have always struck me as being too eagerly

targeted towards children (“our future

benefactors!”). Displays have usually been arranged on plinths set way too

low for the average adult, and the information provided has been dumbed-down to

a sixth-grade reading level: “see the

Incas”; “see the Incas run”; “see the Incas die horribly from imported Spanish

smallpox”. To my satisfaction, this time things were different. After all,

this was a display of the collection of the Heritage Museum of St. Petersburg,

and it was good to see it getting the approach it deserved.

Alexander

has copped varying press over the years – sometimes he’s “Great”; sometimes

he’s anything but. At the moment, he’s going through an image renovation, but

there is still a big faction of people out there who think of him as “Alexander

the Not-All-That”. This exhibition plumbs the depths of his media hype (by

means of Lysippus the sculptor, for one) and the poison pens of later historians

and current film-makers. There were fascinating things to see – many of them

famous in their own right, like the Gonzaga cameo which graced the cover of my

Ancient History textbook in school and which hit me with a fair degree of

startling recollection.

However,

these shows bring out my curmudgeonly side. I understand that children have

different attention spans and needs at these events; there’s a level of

comprehension and understanding that’s required to really reap the benefits of

such a showing. I understand this. Do

most parents out there? No. Not if

this experiment was anything to go by. It bewilders me to watch children

carrying on like pork chops while their owners stand idly by muttering futile

things like “now now, Tarquin”, or “be still, Jocasta”. I watched a

six–or-seven-year-old boy banging violently on a glass case while screaming “this is BORING!” and all his mother

could do was to murmur, “hush Tommy: Mummy’s trying to look”. Seriously: if I

had carried on like that at his age, I wouldn’t be alive to write this today.

What

is it about this post-Slap, hands-off,

time out, “I’m going to count to five” parenting style nowadays, that says

children mustn’t be taught good manners? This wasn’t the only badly-behaved kid

present by any stretch of the imagination; in fact they were in the majority.

It’s as if parents have developed a gulf between themselves and the children:

monitoring them and controlling them has somehow become someone else’s duty and

responsibility. And I’m not talking about corporal punishment either: the two

kids who were part of our team were

perfectly well-behaved and interested, and only because we adults had bothered

to engage with them and not treat

them like an annoyance interrupting our day’s activity. Anyway, it was all enough

for me to go, “you know what? I’m just going to buy the exhibition catalogue in

the Museum shop and forget about trying to see it first-hand.”

Take

my advice and take a day off work mid-week, outside of school holidays, to go

and see this: you’ll save yourself a huge headache.

Not

that there weren’t any bad-mannered grown-ups there either (and by that I mean apart from the children’s parents, who

by default and their culpability are understood

to be bad-mannered). There was a wheelchair-bound woman who, I swear, if she

ran over my foot one more time while cutting in front of me, was going to get a

clip around the ear. People: not only stupider and more pig-ignorant than you

imagine, but stupider and more pig-ignorant than you can imagine.

Inevitably,

I left this Sartre-an vision of Hell, and went upstairs to chill out with the

dinosaurs. Here too, there was an excess of intemperate, badly-behaved little

oiks and their ‘minders’ (so-called), but at least they were more spread out.

The Museum staff have (wisely, in my opinion) set up a little cafe on this

floor and, inevitably – because noise levels were much diminished beyond its

portal – I drifted inside. To my instant delight, I found that there was a

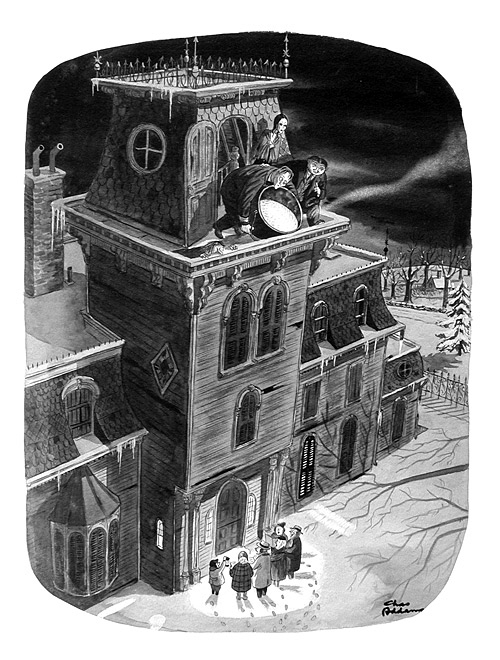

Charles Addams exhibition in progress here, care of the Tee and Charles Addams Foundation. This was more like it: coffee,

no brats or whingeing adults and the artwork of Addams the Great!

As

a kid, much to the mortification of my parents, I was a great and instant fan

of the Addams Family. Not the TV show (although I loved that too), but the

cartoons: my grandparents had a copy of a Chas Addams collection of strips from

the New Yorker and I would thoroughly

enjoy leafing through it. It had just the right twisted quirkiness, coupled

with playful impishness to appeal to me. Frustratingly, the book would vanish

for long periods of time only to be discovered again in odd corners of the house;

nowadays, I recognise this as an effort by my carers to limit my exposure.

Ironically, it only served to increase my interest.

The

fun part of Addams’ work is that it’s often very subtle; unless you are quick

to spot the strangeness, it can slip by completely unnoticed. On display at the

Museum was one of my favourite cartoons entitled “Planetarium”: unusually, for Addams, this is a strip rather than a

single panel. The audience at the planetarium enter and sit down; they watch

attentively as the lights dim and the ‘stars’ emerge; an image of the moon

appears, waxes full and then wanes to a crescent before the lights come up and

everyone walks out. If you don’t look closely, it doesn’t make much sense; if

you do, you see the little man in the second row break into a sweat and

transform into a horrible creature as the ‘moon’ grows and diminishes, before

resuming his natural state and leaving with the rest of the crowd. Like the

un-careful viewer, they miss the transformation too.

I’d

seen most of these images before but it was a delight to see the originals in

close up. I never realised that much of the white space in a typical Addams

cartoon is highlighted with white ink and that this medium is often used for

correcting errors in inking the final work. I mean, it’s only logical when you

think of it, but since Addams is, like, a god to me, I’d just assumed that his

works sprang fully-formed from his brow, as Athena did from Zeus’s.

The

inky blackness of the typical cartoon is not a uniform shade either, as many of

the New Yorker reprintings imply.

Rather, there is a subtlety and gradation in the monochrome ink washes that

lends the works depth and dimension. It’s kind of like seeing the original of a

favourite print and realising that there are brush strokes visible on the

canvas that can’t be discerned in the reproduction.

Ironically,

viewing all these stodgy bankers, their wives and their Boy Scout offspring

falling victim to the freaky Addams Outsiders made me think more intensely of

the bad-mannered families below in the main exhibition: I could imagine some of

them encountering their come-uppance in the form of a grinning Uncle Fester spawned

machination some day! (Not that I would wish something like this on anybody.

Not really. Except maybe Tommy...)

All-in-all,

much as I enjoyed the displays (not the experience)

of the Alexander exhibition, this was

the highlight of the day for me and I left the ‘Repository of the R’lyeh Idol’

(ie. the Australian Museum) with a sense of completeness and well-being.

Oh,

and the Alexander catalogue!

No comments:

Post a Comment